‘Banished’ details brutal ousting from rural South

Kam Williams

It’s a phrase that has become so common that most of us don’t think twice when we hear it — how many 20th Century African American trailblazers are referred to as the first to achieve certain feats or milestones “since Reconstruction.”

For instance, Edward Brooke, R-Mass., is always called the first black elected to the U.S. Senate since Reconstruction. Similarly, when Virginia Democrat Douglas Wilder is celebrated, it’s almost always as the first African American to serve as governor of a state since Reconstruction.

So why is that “since Reconstruction” qualifier so frequently attached to modern African American accomplishments? Because blacks had briefly made significant inroads in American society following the Civil War, only to have everything taken away in the wake of the rise of the Ku Klux Klan.

Between the late 1860s and the 1920s, black people were subjected to what can only be called a form of ethnic cleansing. That reign of terror, which lasted over half a century, partially helps to explain the geographical demographic pattern that resulted in black people being packed into the country’s urban centers.

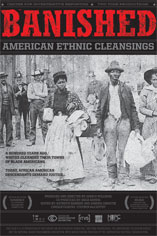

The heartbreaking documentary “Banished: How Whites Drove Blacks Out of Town in America” uncovers this long-hidden aspect of U.S. history.

The picture was directed by Marco Williams, an intrepid researcher who often put himself in harm’s way as he crisscrossed the South and Midwest to ask the tough questions and to unearth proof of a widespread pattern of purging blacks from rural communities — a pattern that persists to this day.

The evictions typically began with a lynching, followed by threats being leveled against every remaining African American in the county at gunpoint. They were forced to flee before sunrise with little more than the clothes on their backs, often abandoning homes, businesses and farms they owned.

Told never to set foot on their own property again unless they also wanted to be lynched, these refugees left, feeling lucky just to be alive. The expulsions were invariably followed by the adoption of “whites-only” residential policies.

In “Banished,” Williams accompanies some still-frightened descendants of the disenfranchised back to visit their ancestors’ estates. We see that many of these counties remain lily-white, such as Forsyth County, Ga. There, Williams interviews Phil Bettis, an unsympathetic attorney who admits to helping Caucasians take legal title to the lands once owned by black citizens.

“They slept on their rights,” Bettis rationalizes, blaming the victims. Ironically, this same man is the head of the local “biracial committee,” which is looking into whether the relatives of the banished blacks ought to be eligible for any reparations. If I were one of those relatives, I wouldn’t hold my breath.

Many say that the South has changed significantly in the years since abolition and desegregation, but you wouldn’t know it from watching “Banished.” Williams makes a different case, making his film a jaw-dropping shocker that you have to see to believe.

“Banished: How Whites Drove Blacks Out of Town in America” will premiere tonight at 6:30 p.m. at the Human Rights Watch Film Festival in New York City. For more information about the film or the festival, visit www.hrw.org/iff/2007/ny/films.html#2.

|

| The new documentary by intrepid researcher and filmmaker Marco Williams, “Banished: How Whites Drove Blacks Out of Town in America,” details the purging of African Americans from rural southern communities from the Civil War era to the present. (Photo courtesy of Two Tones Productions) |

|